PBM Reform: The Biggest Healthcare Potential Shakeup of 2025

Thinking through what it may look like and who might benefit

As we move through 2025, one of the most significant healthcare policy battles could be the reform of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). With rising scrutiny from legislators, regulators, and the public, PBMs—once the silent intermediaries in healthcare—are now at the center of a debate that could change the pharmacy landscape over the next several years.

Lina Khan at The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is deep into an investigation of PBMs, bipartisan lawmakers are pushing for more pricing transparency, and major healthcare stakeholders—ranging from drug manufacturers to insurers—are weighing in on the future of PBM regulation. All of this is setting the stage for a high-stakes showdown that could lead to fundamental changes in how prescription drugs are priced and reimbursed in the U.S. Given their position in controlling reimbursement prices for retail pharmacies, owning large mail order pharmacies, and heavy leverage in negotiating with manufacturers. With this backdrop, I believe the next 18 months are going to be a key turning point in how we acquire and price drugs domestically. I will take a look at the possible outcomes and some of the winners and losers along with some information on the stakeholders size in the market. I will aim to leave out the GPO portion of the business model in an attempt to simplify the article.

What is a PBM?

Many Americans have heard the word PBM (Pharmacy Benefit Manager) as it is constantly thrown around as a culprit in the high drug prices that we all pay along with pharmaceutical manufacturers. However, as I pointed out above, the PBM does provide value and is basically outsourced Part D benefits for a health plan/employer group. I had a well respected person in the industry once tell me “don’t let anyone tell you fool you, these people like PBMs as they make their life easy on a lot of fronts”. I thought this was an odd statement but one that has stuck with me over the past 7 years.

With thousands of different drugs approved by the FDA to choose from, many health plans need assistance in being able to pick the best combination of drugs for their beneficiaries while balancing cost and clinical value of each drug. The drug appraisal process is also accompanied by a utilization management function where the PBM will do the cost containment on the best drugs while approving or denying drugs based on clinical need or medical policy. Additionally, the health plans/employer groups do not want to manage a network of 65,000 pharmacies with contractual agreements in order for their beneficiaries to be able to get drugs anywhere. The third leg of the stool is really pricing power as a regional Blue Cross Blue Shield plan of 2 million beneficiaries can join forces with a large PBM of 50 million beneficiaries to use leverage to buy drugs at a cheaper price for their employer groups or beneficiaries. For these reasons, my friend who made the remark is right, the PBM does provide value and had great intent at the inception of the idea…. To keep drug prices lower.

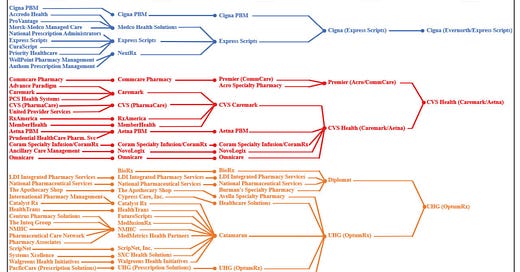

Where it May Have Gone Off The Rails

PBMs had been in the US system since the 1960s but became a large influencer in the market in the late to mid 1990s as a large swath of generic drugs became available. During that period you had Zantac, Prozac, Prilosec, and Claritan all go generic which created a situation where the rebate dollars for branded drugs would fall off a cliff for the PBM. In the place, many of the manufacturers would begin offering enhanced rebates for “formulary positions” to keep their sales up but also help the PBM generate income. At some point after this period, the rebate became the KPI by which employers and health plans would begin to assess the PBM effectiveness in reducing prices. Fast forward to 2009, when the early drafts of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will begin to have a Medical Loss Ratio requirement for insurance companies which mandated the spend 80-85 cents of every dollar taken in premium to be spent on the care of the subject beneficiary. Once this became more evident to be reality, many of the largest health plans started to consider the strategy of vertical integration. The law said they had to spend 80-85 cents of every dollar taken in insurance premium on care of the patient but did not stipulate that the insurer could not own assets which the 80-85 cents was spent on. As a result, UnitedHealth Group ended up buying Catamaran in 2015 to become OptumRx, Cigna ended up buying Express Scripts in 2018 and CVS acquired Aetna in 2018 to go along with Caremark. Today, those three PBMs (Express Scripts, Caremark and OptumRx) are about 80% of the entire PBM market and all three are owned by publicly traded companies which are graded on top line growth and margin every 3 months by the public markets. For this reason, it is widely believed that these PBMs are no longer incentivized to drive drug savings as manufacturers continue to raise WAC prices for drugs to provide more rebate dollars for the PBM. Below is a chart from the FTC investigation showing the progression of consolidation and the overall size of the PBMs by market share.

Some of that may or may not be conjecture but I wanted to provide both sides of the argument in an attempt to provide context to the argument. That being said, we are seeing the retail pharmacy channel fall apart, drug prices rise and frustration across multiple stakeholders which has garnered quite a bit of attention on the PBMs in the US.

Why Reform is Inevitable?

1. Legislative and Regulatory Pressure: Congress has introduced multiple bills aimed at increasing transparency and eliminating rebate-driven distortions in drug pricing. Both Democrats and Republicans are in rare agreement that PBMs hold too much power over the flow of money in the prescription drug market. Typically, I would be very skeptical of any real reform but this is the first time that I have seen this type of bi-partisan support paired with FTC scrutiny that I believe is making the perfect storm for change.

2. Manufacturer and Payer/Employer Frustration: Following along the lines in the above context, drugmakers argue that PBMs inflate drug costs by demanding massive rebates to secure formulary placement. Health plans, on the other hand, increasingly rely on PBMs to negotiate savings but worry about conflicts of interest when PBMs also own mail-order and specialty pharmacies. We are seeing abrasion in the healthcare economy being reported by multiple stakeholders with frustration being tossed on the PBM whether misguided or not.

3. Consumer and Pharmacy Backlash: The killing of the UHC CEO and the online reaction to it have completely disgusted my view of humanity over the past several months but this has made a mob mentality against UnitedHealth which is very real. Additionally, we are seeing some high profile players like Mark Cuban move into the space with a motivation of fixing the perverse incentives that continue to drive up drug prices. This has brought the spotlight on the PBMs along with independent pharmacies that continue to close nationwide. These retail pharmacies claim PBMs are driving them out of business through aggressive reimbursement cuts, while patients are frustrated by high out-of-pocket costs that don’t reflect the rebates PBMs negotiate behind closed doors.

I have always thought the idea of PBM legislation was a political talking point which would surface in the form of “tough talk” every political cycle but I am feeling the momentum behind this current movement that I have not experienced.

Possible Scenarios for PBM Reform

Several key reform scenarios could unfold in 2025, each with far-reaching implications:

1. Full Transparency & Pass-Through Model

In this scenario, PBMs would be required to disclose all revenue streams, including rebates, spread pricing, and administrative fees. Many believe this is the best path forward although most of the PBMs claim to be passing through the majority to their downstream stakeholders today. In this new model, insurers and employers would pay PBMs a flat service fee rather than allowing them to profit from undisclosed rebates.

Impact: This could shrink PBM margins but increase transparency, potentially lowering costs for payers and patients.

2. Elimination of Rebates & Shift to a Net Price Model

A growing policy push aims to eliminate the traditional rebate system, where PBMs negotiate discounts with manufacturers but retain a portion of the savings. Instead, PBMs would shift to net price contracts, ensuring:

- Drugs have a single, transparent net price rather than being subject to back-end rebates.

- Point-of-sale discounts for patients replace traditional rebates.

Impact: This could lower out-of-pocket costs but raises a critical challenge that I mentioned above—PBMs need privacy in their negotiated pricing to avoid price erosion across contracts.

How PBMs Could Preserve Pricing Privacy in a Net Price System

PBMs have historically kept their negotiated rebates confidential to prevent manufacturers from price-matching across different PBMs. To transition to a net price model while maintaining confidentiality and leverage, PBMs might:

Implement Private Price Clearinghouses – A third-party intermediary could verify net prices without publicly disclosing individual PBM discounts, similar to a financial clearinghouse.

Average Net Price Reporting – Instead of PBMs disclosing individual prices, they would report blended national net prices, ensuring manufacturers retain the flexibility to negotiate different rates.

Tiered Pricing Structures – Manufacturers could provide volume-based tiered pricing to PBMs, allowing for differentiation without direct disclosure of competitive rates.

Flat Service Fees Instead of Rebates – PBMs would charge a transparent administrative fee per prescription rather than earning a percentage of negotiated rebates.

This transition could maintain confidentiality while eliminating the distortions caused by rebates.

3. Breaking Up Vertical Integration

Given the context I provided around MLR and the ACA, lawmakers could force PBMs to separate from their parent insurance companies (e.g., UnitedHealth’s OptumRx, Cigna’s Express Scripts). While this will be very sticky and clunky in the near term, it would be beneficial over time to help some of these businesses protect themselves from litigation while also helping avoid potentially perverse incentives that arise in the system.

- Restrictions could be placed on PBMs owning specialty pharmacies, limiting their ability to steer patients toward their in-house businesses.

Impact: Would reduce potential conflicts of interest but could also disrupt the integrated cost-control strategies many insurers use. Could also stop the rebate accumulation as a KPI for potential new customers which could contain the WAC price hikes.

4. Federal Regulation of PBMs

I am not a fan of this as the federal government has historically struggled in the market with publicly traded companies which typically results in quite a bit of bureaucracy. In this scenario, PBMs could face government-mandated limits on service fees and spread pricing.

- Transparency requirements could force disclosure of how formulary placement decisions are made.

Impact: Would give regulators more control over drug pricing but could slow down contract negotiations and formulary updates. Could also end up creating perverse incentives and long contracting/bid cycles given the governments traditionally slow nature.

5. Government Takeover of Drug Pricing for Public Plans

I am also not a fan of this option either as expanded government reach in healthcare historically has struggled. For this article Medicare and Medicaid could move to directly setting drug prices rather than allowing PBMs to negotiate. PBMs would be reduced to claims processors rather than price negotiators.

Impact: Would significantly reduce PBM influence but could disrupt the private drug market if commercial payers push back against similar policies. The government has not been all that effective of a negotiator as we saw in the IRA negotiations last year.

Who Wins & Who Loses in PBM Reform?

This is a very difficult question to answer as the variety of unintended consequences in healthcare often make it a challenge to predict. That being said, below are some of the predictions and ironically some of the stakeholders end up on both the winners and losers list.

Potential Winners:

Drug manufacturers- If rebates disappear, it could provide a more traditional system of the actual cost of drugs. Whether manufacturers will be able to get more net cost will be debatable as many of the PBMs will still have some sort of bid process to force the best price. However, they would be the winner as it would begin to stop increasing the gross to net bubble (coined by Adam Fein) which has the WAC prices increasing every year. This could finally take the pharmaceutical manufacturer greed out of the talking points for escalating WAC pricing year over year.

Independent pharmacies- Given some of the “pharmacy deserts” that have been created over the past 5 years as many of the independent pharmacies are closing/struggling to get enough buying power from wholesalers to create margin as their PBM contracts reimburse less and less. Baby boomers will want to gravitate towards a local independent pharmacy as they will want a relationship with their pharmacist as the number of meds these aging seniors will be taking. I think this channel could be a big winner if the legislation addresses some of the low PBM reimbursement.

Retail Pharmacy Chain- For similar reasons to the independent pharmacy, much of the retail pharmacy infrastructure is struggling. Given the real estate outlays to run a strong retail pharmacy, the need for margins are a must to remain financially viable. Even some of the larger retail brands like CVS, Rite Aid, and Walgreens are struggling to create delta between what they buy the drugs for and what their retail PBM is willing to reimburse them. Some strong legislation could help save the retail chain as it may enhance reimbursement from the PBM or even force them to leave the mail order pharmacy channel.

Patients/Employers- Patients and employers would win over the long haul as WAC prices should theoretically fall. Greater transparency and rebate reforms could mean more of the prescription drug savings would reach them instead of middlemen, easing affordability. Likewise, curbing restrictive or potentially self-serving PBM practices (like exclusive networks or formulary games) should improve access to treatments. While there could be secondary effects (such as premium adjustments higher), the net effect of a potential 2025 PBM reforms would be to reduce patients’ financial burden and improve access, aligning the system more with patients’ health interests. I may end up putting these stakeholders (patient/employer) on the losing list as well as it could mean that the new PBM system does not provide as much leverage/savings in the near or long term.

Generic and Biosimilar Manufacturers- Generic and biosimilar manufacturers could also be clear winners under PBM reform. Their business model (offering equivalent therapy at lower cost) many believe has been undermined by rebate-driven formulary preferences in the status quo. Traditional thinking believes that reforms that enhance transparency or remove rebates would directly boost their competitive position, likely increasing their market share and revenues. These companies have been vocal in supporting PBM reforms – for instance, calling for transparency and an end to PBM fees tied to list price which underscores that they expect to benefit. In a 2025 landscape with rebate-free, more neutral PBMs, generics and biosimilars could more readily fulfill their promise of savings, making this stakeholder group a financial winner in most reform scenarios.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Healthcare Economy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.